Unemployment and market frictions in France

After my recent experience of job hunting in France, I can report on the organization of the job market in France, its structure and organization. I found that there are a lot of frictions in this market and some of the frictions are due to the excessive weight of regulation.

First, I was quite surprised that, contrary to the popular perception, there aren't many intermediaries: aka recruitment agencies that you can contact, and that know which skills are required and direct you towards the right people. Hence, it seems like most of the time, firms contact potential candidates directly. Although it may seem like bypassing an intermediary speeds up the process, actually firms then loose the screening abilities of recruitment firms, which may then result in suboptimal outcome. In my opinion, recruitment firms also don't use enough their personal connections to anticipate future demand and then to propose their candidates before a formal job vacancy ad is posted. Of course this analysis would need to be done more scientifically on a representative pool of agents, but this most likely points to a lack of efficient intermediaries in the job market. In economic terms, I would say that there are large frictions in the job market that lead to persistent unemployment. Naturally, those frictions are exacerbated in times of reduced economic activity - as is the case in the French financial sector - and that's why France has a high unemployment rate of more or less 9%.

One of the reasons why intermediaries have found difficult to develop in this market is probably due to the excessively high burden of labour regulation in France. The "Contrat à Durée Indeterminé" (CDI) - undetermined duration contract - is strongly biased towards the employees and makes it difficult for companies to lay off workers when they have to. Companies are as a result very wary of hiring people with this contract and sometimes prefer not to hire additional staff.

Peter A. Diamond, Dale T. Mortensen and Christopher A. Pissarides received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2010 for their contribution to labour economics. They created search-and-match models that explain why there can be both unemployment and job vacancies at the same time. The driving force behind those models is the fact that job searching (or from the point of view of the firm candidate finding) is costly in time and effort.

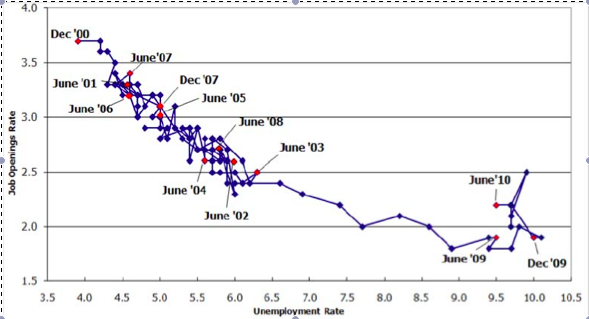

As a result of search frictions, the market outcome is inefficient: companies don't fill all their vacant positions and unemployed people don't find a job at the same time. The inefficiency comes from the fact that there exists two externalities: congestion externality - by searching harder, the individual worker makes other unemployed workers worse off by reducing their job finding rates - and thick market externality: by searching harder, the worker makes employers better off by increasing the rate at which they can fill their vacancies. The Beveridge curve shows the relationship between unemployment and vacancies. (cf. graph below) Because there are externalities, economic theory tells us that there is room for public intervention to improve the market. The role of the state should thus be to reduce those frictions by making it easier for employers and jobseekers to find themselves and agree on an employment contract. Examples of bad solutions are contracts like the French CDI that, by making firing more difficult ex-post, reduce the incentives of the firms to hire ex-ante. Similarly, increasing unemployment benefits increases unemployment by reducing the incentives of job seekers to find and accept an offer.

Looking at the dynamics helps us understand why unemployment can stay persistently high. The response of unemployment to an adverse shock (say in productivity) will be faster and sharper than the response to a positive shock. The reason for this asymmetry is that an adverse shock results in an immediate increase in job separations and thereby to an up-ward jump in the unemployment rate. On the contrary, a positive shock leads to a gradual fall in unemployment driven by the time-consuming hiring process.

For a survey of the labour models developed by Diamond, Mortensen, Pissarides et al, the reader familiar with economic theory can read the scientific background compiled by the Royal Swedish Academy of Science.

Comments

Post a Comment