Greek crisis: no job, no money, no problem

Seven years after the beginning of the Greek debt crisis, which started with newly elected Prime Minister George Papandreou discovering that Greek government budget numbers had been manipulated for years, is Greece out of the woods yet? Let's have a look at the latest economic data to see what has been the results of three bailout packages (2010, 2012 and 2015) and seemingly endless political drama. Did Greece choose the optimal path by opting to stay in the Eurozone or would it have been better off exiting the Eurozone in 2010?

1. The depression

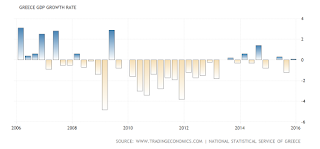

Between 2008 (when the global financial crisis propagated to Europe) and 2014, Greek GDP has collapsed by one third. This is huge, and even though it is not as bad as the Great Depression (between 1929 and 1933, US GDP dropped by 45%), it ranks as one of the worst depressions of any developed economy. In fact, ratings agency S&P has even downgraded in 2014 Greece from developed economy to emerging market status, which is the first time ever that such an event happened.

Latest GDP growth numbers show that the economy has stopped falling, but there is no recovery either.

Part of this collapse can of course be explained by the Eurozone itself that has also suffered from a recession. To extract the specific Greek shock, we looked at the ratio of Greek to Euro area average GDP per capita. After a catch-up period between 2001 (adoption of the Euro) and 2009, the ratio dropped from 77% to 54% in 2014 during the current depression, which represents a 30% drop and Greece has been overtaken by both Slovenia and Portugal. Hence most of the economic shock cannot be explained by the recession of its partners.

Source: World Bank and own computation

2. Jobs have gone, and workers too

Picture taken in May 2016 in Thessaloniki

As it is often the case in European countries with inflexible labour market, the economic downturn resulted in massive unemployment. Currently at 24.4%, the unemployment rate is declining, but at a painfully slow speed of 1.5% per year. At this speed, it would take another 12 years to get back to the pre-cris level of 7.3% (2009), assuming this is the (already high) structural unemployment rate.

Because it is so difficult to find a job, a lot of Greeks are using the freedom of movements in the European Union to try and find a job abroad, and Greek population is shrinking. Greece has lost 767,000 inhabitants per year in the last 3 years, which represents for a population of less than 11 million people, a loss of 0.7%pa. This is dramatic knowing that on the same period, the EU population grew at a rate of 0.3%. It seems that the Syrian refugees, who landed en masse on Greek coast, all opted to carry on their journey to other European countries.

In 2009/2010, when discovering the dramatic fiscal situation that his country was in (government budget deficit was expected to reach 12.5% of GDP because of misreporting by the previous government), Prime Minister George Papandreou had two possible paths to get to a fiscally balanced situation: stay in the Eurozone and embark on an internal devaluation on an unprecedented scale or leave the Euro. As discussed in a previous article , other countries in the Eurozone had significant interest (both political and financial) in Greece staying in the Eurozone, and successfully managed to pressure the Greek government to stay in the Eurozone. As we can witness now, the decision to stay in the Euro had massive consequences and it is striking that it was taken without a referendum or any other form of public consultation. As a reminder, most American economists (and they were more objective than European economists because they didn't have home country interest bias) like Paul Krugman, were advocating at the time for "Grexit".

One important aspect of an internal devaluation is the reduction in prices and labour costs. Greece is still firmly in deflation for the third year. This is the longest period of deflation in Greece’s history since 1960 and suggests that Greece has not finished with its structural adjustment yet.

A brighter spot is the current account, where the deficit went from 14.9% of GDP in 2008 to 0.2% in 2015, which means that Greece is close to not being a net borrower to the rest of the World anymore.

| Year | Current Account Balance (% of GDP) |

|---|---|

| 2006 | -11.4 |

| 2007 | -14.6 |

| 2008 | -14.9 |

| 2009 | -10.9 |

| 2010 | -9.9 |

| 2011 | -9.9 |

| 2012 | -4.2 |

| 2013 | -2.2 |

| 2014 | -3.0 |

| 2015 | -0.2 |

4. No money

Coming back to the 2nd part of the t-shirt joke "Greek crisis, no job, no money, no problem", Greece is indeed close to being bankrupt. The three bailout packages funded by the IMF and European Union amount to more than the GDP of Greece: 110 billion Euros in the first package of 2010, 136 billion Euros in the second package in 2012, and 86 billion Euros in 2015. Despite this huge effort, Greece still has a 7.2% government budget deficit in 2015. What has gone wrong compared to the successive bailout plans?

One possible explanation is the bad situation of the financial sector and the negative feedback loop effect that it has on the economy: when banks have non-performing loans and little capital, they have to reduce their lending, which depresses economic activity and further increases the ratio of non-performing loans. The only solution for the state to break this loop is then to recapitalize the banks. To support this story, we compare the actual government budget deficit with the figures from the 2010 bailout programme provided by the European Commission.

| Government balance | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 Plan | -8.0 | -7.6 | -6.5 | -4.9 | -2.6 | |

| Actual | -11.2 | -10.2 | -8.8 | -13.0 | -3.6 | -7.2 |

| Difference | -3.2 | -2.6 | -2.3 | -8.1 | -1.0 | |

| Bank recapitalisation (in excess of 2010 plan) |

2.7 | 10.6 | 4.2 |

We can see that some of the excessive deficit can be explained by the need to recapitalize banks more than was initially forecasted (I don't have the numbers for 2011 and 2014).

As a result, debt has grown to a level of 177% of GDP, which is most likely not sustainable (Reinhart Rogoff [2010, Growth in a time of debt] have shown that above 90% of GDP, debt becomes a very significant drag on economic growth). By calling for a debt relief as part of any new bailout package, the IMF is now calling the previous loans for what they always were: subsidies, not loans. It makes sense economically to have transfers (meaning cross-countries subsidies) in a currency union, but it causes two problems, one political and one technical. The political problem is that European political leaders have promised that the loans would be paid back, knowing that they would not be, which is the definition of lying. Secondly transfers are technically not allowed within the Eurozone according to the Maastricht treaty. Leaving aside the legal hurdle - when there is no other solution, you do what you have to do - , it exposes a structural flaw in the currency union.

5. Conclusion

To conclude, Greece is not and won't be in the near future back to a healthy situation, as there are still more dark clouds than positive news. The situation is definitely improving, but permanent damage has been suffered: some of the jobs (skills), companies and people that are gone might never come back. I cannot definitely show that choosing another path would have resulted in a better outcome, but it is difficult to imagine how it could have been worse.

Some sources:

Great Depression statistics: http://www.shmoop.com/great-depression/statistics.html

Bailout packages and background: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_government-debt_crisis_timeline#Government_Budget_Balance_and_Debt

New analysis by FT's Martin Wolf

ReplyDeletehttp://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/9452f446-2c01-11e6-a18d-a96ab29e3c95.html#axzz4AzTda3Vx